He liked to say that one needed to write a million words before one could be a writer. He told us that discipline was far more important than mere talent. There were no distractions on a ship, in particular no telephones.ĭischarged after 20 years, he resolved to become a writer and moved to the Village. He confessed that he was most productive writing at night at sea and often booked passage on freighters to meet deadlines. He had dropped out of college to sign up as a mess boy and, after an article he wrote about his experiences aboard ship caught an admiral’s eye, was eventually promoted to the position - created just for him - of chief journalist for the service. He proudly described how he started out in the Coast Guard during World War II, as the Black Cyrano de Bergerac of the South Pacific, writing letters for his lovesick shipmates to send to their sweethearts.

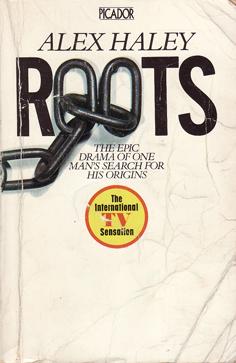

It was a no-nonsense course about the nuts and bolts of being a professional journalist - as Haley was at the time - and he often peppered his lectures with vivid anecdotes from his early days as a writer. Haley” to us he called me “Hearn.” He enjoyed the conviviality of college life and had enormous faith in young people, but his class was not the place for moody poets or budding novelists. Stylistically, he was old school, precise and a bit formal. Haley seemed to be making it up as we went along. The class was rather free-form - not exactly what Hamilton students were used to. Attending Haley’s class allowed me to observe him in action for nearly a year while he was working on his magnum opus, “Roots.” (She signed her letter “Cindy X.”) The book blew me away, just as Ralph Ellison’s “Invisible Man” and Eldridge Cleaver’s “Soul on Ice” did later. I was already familiar with “The Autobiography of Malcolm X,” his collaboration with the Black leader, which had become an instant best seller when it was published three years earlier my sister had read it at Skidmore College and wrote to me about how powerful it was. When I entered Hamilton College in the fall of 1968, I was determined to be a writer, so I signed up for Haley’s writing course, not knowing what to expect. Haley was eternally grateful for such generous encouragement from the distinguished author.Īlex Haley, whose centenary we mark this year, was my James Baldwin. Only James Baldwin replied, showing up at Haley’s place unannounced one afternoon and chatting with him.

In 1959, long before his books “The Autobiography of Malcolm X” and “Roots” made him famous, an aspiring writer named Alex Haley, fresh out of the Coast Guard, wrote to six prominent Black writers in Greenwich Village for pointers on how to break into publishing.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)